How to take the headache out of Cancel Culture: A beginner’s guide on the toxic effects of society’s new trend.

Introduction:

In an age of technology flourishment, social media rampage, and the ability for almost anyone to have a voice online, cancel culture has become an international phenomenon. Cancel Culture has “to do with the removing of support for public figures in response to their objectionable behavior or opinions. This can include boycotts or refusal to promote their work” (Merriam Webster). A somewhat modern day version of ostracism, cancel culture has made it easy for almost anyone to be called out and shut out of society. Whether online, or in real life, it is possible to be thrust out of social spheres due to minute problems in just seconds.

You’ve probably heard of someone being “cancelled”. Maybe you know someone who has, or have even cancelled someone yourself. Either way, the ability to end someone’s career, or at least contribute to it, has become a toxic way to solve issues. I made a poll and had my classmates, hall-mates, and friends from home take it, to see their thoughts and beliefs about cancel culture. Here is the poll. You can take if you wish:

Create your own user feedback survey

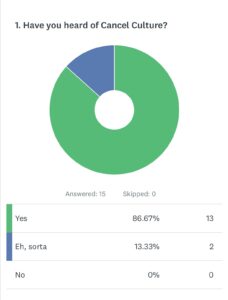

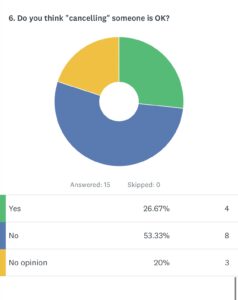

The results told me that most of my friends had heard of Cancel Culture in one way or another. They also recognized the amount of public figures being cancelled today, arguing that social media is the culprit for this wave of call outs. 65% even knew someone personally who had be cancelled and 71% said it altered their reputation. The major question, “Is Cancelling someone OK?” had mixed results with about 57% arguing No, 22% arguing yes, and 21% with no opinion.

Here are a few graphics of the results:

Cancel Culture + It’s Toxicity:

Examples of cancel culture are numerous. Celebrities, politicians, everyday people… the list goes on of people “cancelled”. “Say something wrong, tweet something people disagree with, express an opinion that is surprising or contradicts the established view people have of you, and the demands for you to be fired, de-friended or otherwise driven from the realms of men quickly follow” (Cillizza). Our past president Obama said this himself. Pointing blame from outrage to outrage and controversy to controversy is not creating real change. While many believe the true nature of cancel culture is activism and social change, judging and punishing people for their past mistakes is not activism. Some “people live in shame and denial as a way of self-preservation — an effort to diminish their chances of being called out” (D’Amour).

How is this helpful?

Take, for example, Caroline Flack. Caroline was a famous television presenter from the UK. After hosting the reality show Love Island, tabloids boosted her career and her fame. Then, the bullying started. First, judgement from dating Harry Styles when she was 31 and he was 17. Next, she was charged with assault on her boyfriend which filled the news for weeks. Nicknames, rumors, and malicious reports began to flood Caroline’s life. A close friend of Caroline even said, “she lived every mistake publicly under the scrutiny of the media” (Picheta). Mistakes in Caroline’s life were publicized and seen by whomever wished, adding to any other struggles she had in her life. Twitter also added to the public scrutiny she was facing already, dehumanizing her and creating a level of despair in Caroline’s life that was too difficult to bear. Caroline tragically died this past February, ending her own life.

While the media itself is not all to blame for her death, the amount of trolling, bullying, and misogynistic comments that existed before her death are factors in it. Social media fueled the fire that led to her death. Public commentary and especially cancel culture created a life too hard to bear.

This example displaying the toxic and life-changing effects of cancel culture is powerful enough on its own. Cancel Culture keeps people from learning and growing, speaking up, and engaging with others. The idea of cancelling someone has become a cruel hobby in which the cancellers ultimate goal is failure for those they wish to cancel. It is good in that it “demands social change” and addresses issues and inequalities in society (D’Amour). However, demanding social change by ruining someone’s life is toxic. “The term ‘cancel culture’ may be new, but the human impulses propelling it are old” (Henderson, City Journal). It can get ugly very fast and it does not allow the “cancelled” people to learn from their mistakes.

“People simply derive much pleasure from mobilizing together against a perpetrator, allowing a great feeling of togetherness at little personal cost. Others question whether the brutality of the call-out is always in proportion to the original offense” (Bouvier from Discourse, Context & Media Volume 38). Many people exist, which I would argue, are deserving of being cancelled. Those who committed crimes against the judicial system and people themselves. However, there are also those undeserving of the public shame and humiliation in which cancel culture fosters.

Conclusion:

Instead, I encourage other methods to bring social change that do not include ruining someone’s life or career. There are other ways rather than punishment and cancellation. Fostering ways to combat wrongdoings, addressing them, and instead encouraging apologies, and fighting social silence are more promising measures than cancelling someone. To end, I wanted to include this quote I found from a New York Times article entitled, “I’m a Black Feminist. I Think Call-Out Culture Is Toxic.” The author, Loretta Ross, argues that cancel culture or call-out culture is toxic. She finishes her argument piece with a story of her own experience and fear of being cancelled: “In 2017, as a college professor in Massachusetts, I accidentally misgendered a student of mine during a lecture. I froze in shame, expecting to be blasted. Instead, my student said, “That’s all right; I misgender myself sometimes.” We need more of this kind of grace” (Ross).

– – Works Cited:

Bouvier, Gwen. “Racist call-outs and cancel culture on Twitter: The limitations of the platform’s ability to define issues of social justice,” Discourse, Context & Media, Volume 38, 2020, 100431, ISSN 2211-6958, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcm.2020.100431.

Cillizza, Chris. “What Barack Obama Gets Exactly Right about Our Toxic ‘Cancel’ Culture.” CNN, Cable News Network, 30 Oct. 2019, www.cnn.com/2019/10/30/politics/obama-cancel-culture/index.html. D’AMOUR, ALEXANDRA.

D’Amour, Alexandra.“Cancel Culture: The Good, The Bad, & Its Impact on Social Change.” On Our Moon, 2 Apr. 2020, onourmoon.com/cancel-culture-the-good-the-bad-its-impact-on-social-change/.

Henderson, Robert. “The Atavism of Cancel Culture.” City Journal, Manhattan Institute for Policy Research (MI), 30 Sept. 2019, www.city-journal.org/cancel-culture.

Merriam-Webster. “’Getting Canceled’ and ‘Cancel Culture’: What It Means.” Merriam-Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/words-at-play/cancel-culture-words-were-watching.

Picheta, Rob. “Caroline Flack, ‘Love Island,’ and the Industry of Outrage Surrounding the Star’s Death.” CNN, Cable News Network, 18 Feb. 2020, www.cnn.com/2020/02/17/media/caroline-flack-death-reaction-scli-gbr-intl/index.html.

Ross, Loretta. “I’m a Black Feminist. I Think Call-Out Culture Is Toxic.” The New York Times Opinion, The New York Times, 17 Aug. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/08/17/opinion/sunday/cancel-culture-call-out.html.